I’ve just completed editing and posting Gustav Freytag’s Technique of the Drama to BrianTriber.com. I’ve yet to complete linking the Index to the rest of the text, but I’ll do that gradually. (It’s extremely time consuming and I have other projects that need attention — rest assured it will be done, but a lot of what an index used to do for books has been replaced by the computer’s Find function, so I feel less rushed about it.)

Of course, editing any text is like inhabiting the author’s world more intensely than simply reading it. It provides insight into not only the subject, but a taste of the way the writer thinks and structures (in this case, as was true with John Quincy Adams’ Lectures on Rhetoric and Oratory, the structure of the work was based on the structure discussed in the work.) So, there are a few thoughts unique to Freytag’s Technique that I’d like to share.

First, regarding Freytag and this particular work. There were points — infrequent but noticeable — when I found the text challenging not necessarily because of its subject, but its content. To clarify, Freytag was a product of his generation. As such, there were numerous nationalistic, racist, and sexist references in the text. If taken as a snapshot of the times, one realizes how much Freytag and his colleagues looked down upon female actors, Jews, and non-Germans in the theater setting. He was, of course, unaware of what would come down the pike almost half a century after his death, but as a time capsule, the piece certainly has future echoes of what would happen in Europe under the Kaiser and again under the Nazis.

|

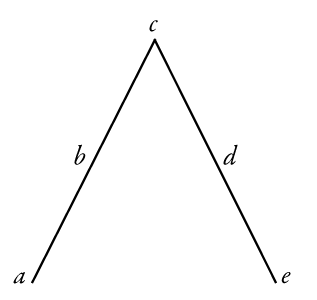

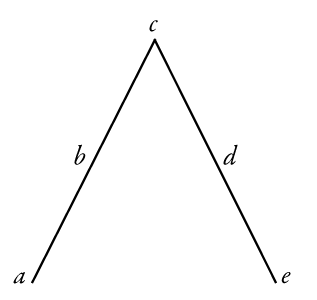

Now, having said that, the book itself is an excellent deconstruction of theatrical arts in Germany circa 1880 or so (the sixth edition was translated into English in 1900). There are a few quirks regarding Freytag’s pyramid (on the right). The illustration, from Chapter 2 of the book, shows his pyramid. The quick breakdown is that each of the lettered nodes represents one of the five acts of the drama. The number of scenes per act is left up to the playwright. What the diagram may suggest (which you must be careful not to interpret it this way) is that the diagram is not only chronological, but also to scale. In other words, that each of the acts appear to take the same amount of stage time. The truth is, as derived from the text, that each act’s performance time is dependent on the number of scenes in the act. So, for instance, The Merchant of Venice is comprised of five acts, but the climax actually occurs about two-thirds through the play, and the catastrophe (more often referred to as the denouement) is the last eighth of the performance time.

|

Parts of the Drama: (a)introduction, (b)rise, (c)climax, (d)return or fall, (e)catastrophe.

|

Shakespearean theater evolved, of course, into other forms in other regions. Eventually German theater, modern English theater, Yiddish theater, and American theater all gave way to the motion picture and its 3-act structure (or 4-act structure, depending upon who you ask). This same 5-act structure finds its way into television, with 4 commercial breaks. This means that the introduction now takes 30 seconds or up to five minutes at the start of the show, the rise around 20 minutes, starting after the first commercial break and bringing us to the middle of the segment after the second commercial break. The climax and return take around five minutes toward the end of this same segment, and the catastrophe completes the show at around 30 seconds following the last commercial break. In film, Freytag’s five acts are broken into approximately 30, 30, 30, 20, and 10 minutes respectively, although with some action films, like the Transformers franchise, the climax is exaggerated into an hour-long spectacle, the return and catastrophe given barely 5 minutes to split between them.

The point here is that the dramatic form has been evolving over time to lean more heavily on the middle of the story, and simultaneously truncating the end of the story. I’m not sure what this says about our viewing habits, wether we’re being re-trained to appreciate a new structure, or whether the marketplace is pressuring film and television to adopt to the viewing public’s changing tastes. After alL, in a world of short-attention-span, it becomes difficult to keep the viewer after the climax has been resolved — once the emotional buy-in for the main characters have been resolved at the climax, how does one keep such an audience’s attention into the denouement? The answer seems to be to truncate the ending. (Television and movie series seem to have a leg up on this since multiple story lines are interwoven and get resolved in different episodes, so the denouement only has to address the main story line of the episode. Torchwood, Season 2 is a good example of this.)

Then the question becomes: do authors adopt their story structure to match the visual media to increase their audience? This seems like a slippery slope, but at the same time, it’s worthy of an experiment. After all, if the goal is to get a message across, shouldn’t it be tailored to the audience? I realize that this can border on agitprop, but there are stories that may benefit from this. Still, there is a reason the novel form still exists as it does, but you’ll notice it is much changed from where it was 75 or 150 years ago. I suppose the real answer will come along in the future, as our media continues to change. Who knows what impact the e-book will have on structure?